This article was originally published in French in “Dragon Spécial Aikido” in January 2018.

Learning an Asian traditional martial art is not neutral. It places us from day one in a lineage, a tradition of which we are finally only a part. As part of this transmission it is common to refer to two types of people: our teacher or our technical referents, and the masters of the past. If it seems obvious to refer to our technical referents, contemporaries who transmit their knowledge and that we are learning from first hand, one can however wonder what can be brought to us by masters who have been deceased for several years when not several centuries.

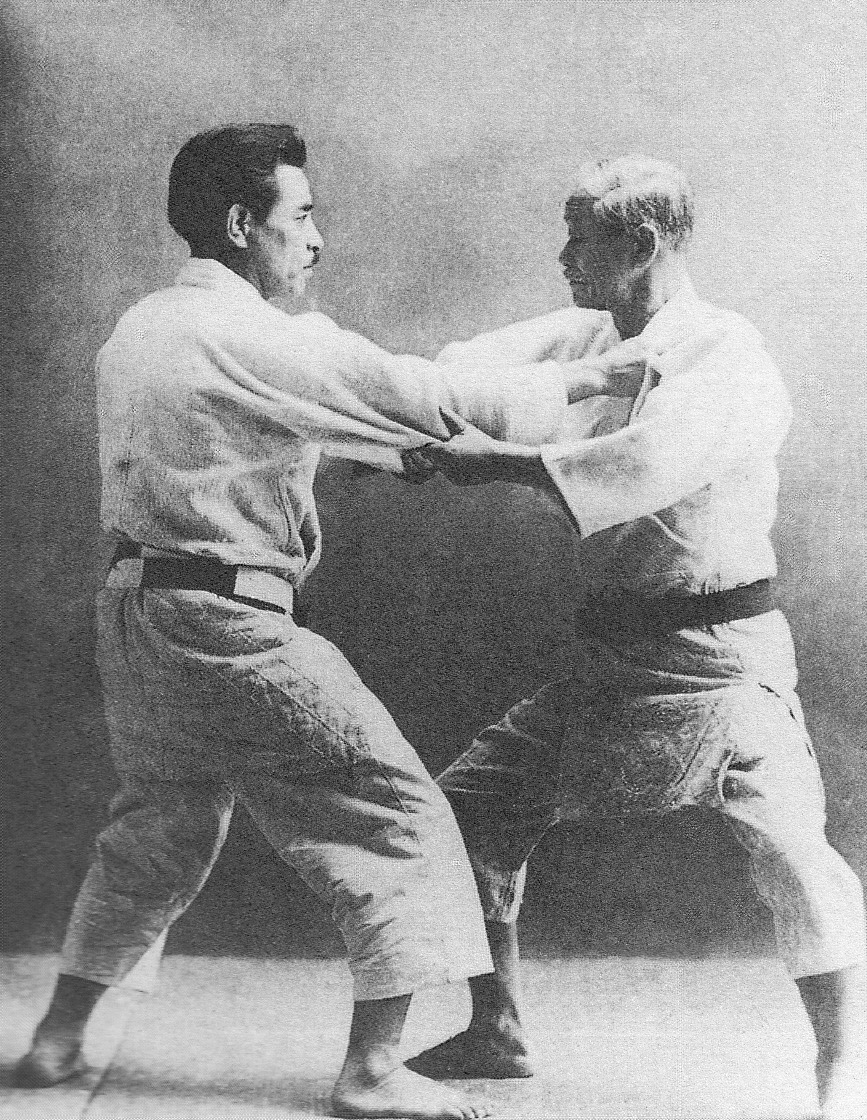

I said that the choice of an Asian martial art is not trivial because it is often linked to a certain image that one has of Japan, China, or the country of origin of the art, whatever it is. The legend of the virtuous Samurai, ready to throw his sword away after disarming his enemy on the battlefield to continue the fight on equal terms remains vivid, as have other a number of other legends. For an Aikidoka, the most universal reference will obviously be the founder, Morihei Ueshiba, to whom will be added the referents closer to the origin of the chosen line. Each school has its founders and pillars which it is fashionable to refer to. Judoka interested in the tradition will talk about Jigoro Kano and Kyuzo Mifune with emotion, Shotokan Karateka of Gichin Funakoshi and probably Taiji Kase if they are living in France. More generally, Budo practitioners will refer quite easily to exceptional adepts such as Miyamoto Musashi or Munenori Yagyu whose works have come all the way down to us.

Why refer to adepts from the past?

Having teachers who are alive and able to teach us, one wonders what is the point of referring to adepts who lived decades ago and whose technique we will unfortunately never be able to feel. It is, however, logical in the context we are interested in, that of a martial tradition, since we seek to walk in the footsteps of those who have preceded us and that it therefore seems useful, if not necessary, to understand what their practices were. With the limitations that we sometimes know.

Far from me the urge to shoot the ambulance, but the reference to Osensei for example can easily make one smile when it justifies choices of practice as diverse as they are opposed. It is obvious that the practice of the founder has evolved over time and that these different practices may legitimately refer to him despite their great differences, just as one can easily accept the fact that it is difficult to justify one’s practice by basing it mostly on the feeling of a person we never met.

Asian martial arts are not the only ones experiencing this issue. If European Historical Martial Arts do not necessarily refer to individuals but rather to Codex face a similar problem since it is primarily a question of interpreting the available sources while accepting that an interpretation is only an interpretation and that without a time machine it will be impossible to obtain confirmation that our understanding is the right one. This does not mean that we should ignore the writings and words that have come down to us, on the contrary.

The masters of the past: between legend and inspiration

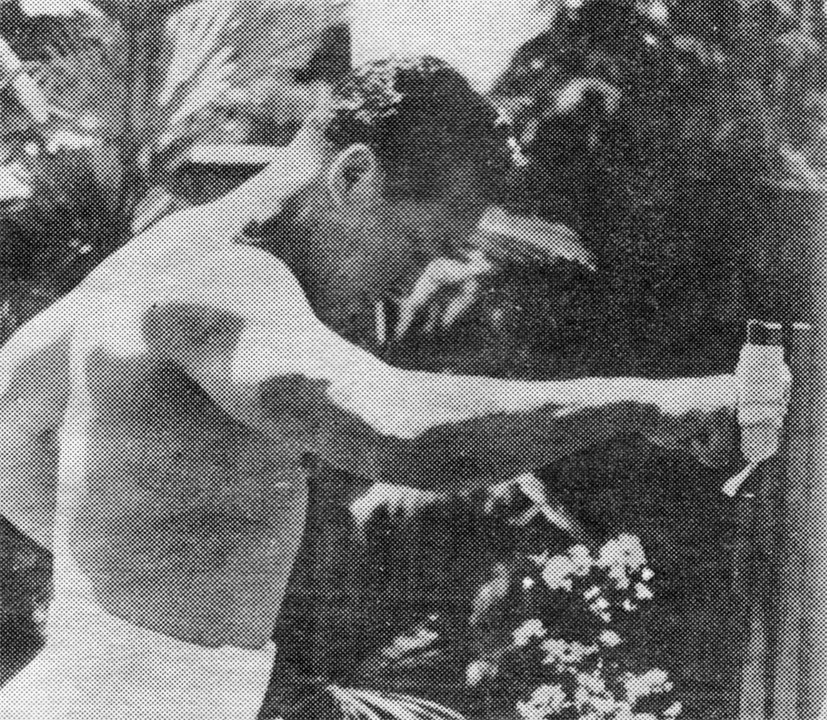

Much information and insights reach us and although they are obviously only partial, they can also be a great source of inspiration as long as we can separate the legend from the reality. The legend obviously has its use, and I probably don’t exaggerate when I say that many of us started martial arts because of these legends. Who has not had the secret hope of seeing the trajectories of bullets like Osensei, or beating bulls with bare hands like Mas Oyama? Beyond the sometimes improved-reality, trying to understand what was the practice of a man, his way of training or teaching, maybe also his way of being in his daily life remain so many keys of understanding for us, modest practitioners on the way.

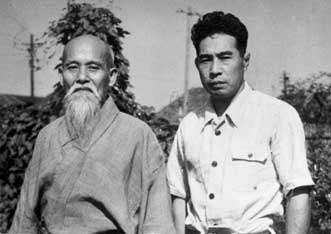

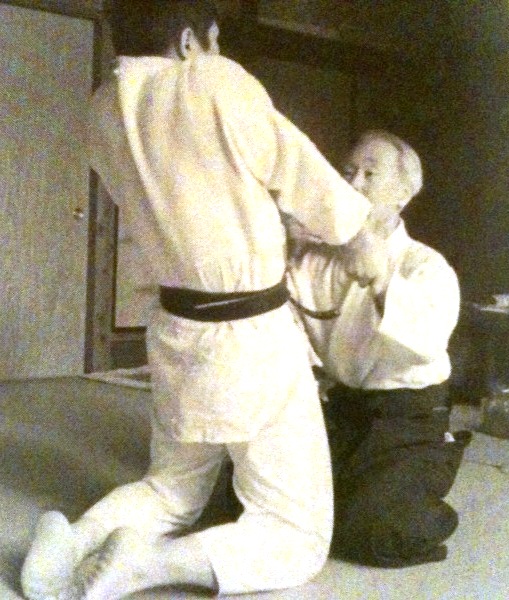

Practitioners interested in the Aiki principle and the origins of Daito Ryu will surely have looked at Tatsuo Kimura’s books on Sagawa sensei, contemporary of Osensei known for his mastery of Aiki, and well-known of Aunkai practitioners since he was one of Akuzawa sensei’s teachers. As a practitioner of Aunkai myself, I recognize these books are never really far from my bedside table and that I refer to the quotes Sagawa sensei on a regular basis. If they made little sense the first time I read them, they did gain some as I improved in my practice and as my understanding got refined. Again when we talk about the masters of the past, and in the absence of direct contact, everything is a matter of interpretation. On the other hand, nothing prevents us from going to meet people who have trained under these masters to obtain first-hand information when possible.

If a legend is about mystification (or marketing), inspiration is a much more positive thing. The feedbacks from practitioners who have been around Osensei are for example unanimous and let us perceive a practice brought to an exceptional level. People who have received his technique are, of course, increasingly rare as time goes by, but some of the adepts the most advanced among us are in turn considering as contemporaries are in turn becoming “masters of the past” for the new generations who arrived too late to meet them.

The masters of the past: precursors paving the way for us

The images and words of these masters are an invitation to explore martial arts practice with the utmost conviction, not to work as an archaeologist to understand how to reproduce exactly what was the practice of a man at a T-time. One thing the greatest adepts have taught us is that their practice has continuously evolved. When I look at the people behind the arts I practice, Mochizuki sensei (Yoseikan Aikido) and Sagawa sensei (Daito Ryu Aikijujutsu), I see men who have never stopped searching, deepening, changing the teaching they received, and that would have continued to do so had they gotten a chance.It is because they refused to see martial arts practice as a dogma, and chose to evolve that we still talk about them decades later. If Morihei Ueshiba had just taught Daito Ryu the way he received it from Sokaku Takeda, would anyone speak of him today?

Based on this observation, we must follow the example of these masters, embrace their will to go further, in order for us to go further than they did and not simply copy them, and perhaps one day become ourselves “Masters of the past”.