This article was initially published in the French Magazine Dragon Spécial Aikido in April 2019.

This simplistic vision of Aikido is generally negatively connoted, grabbing wrists being considered unrealistic by a large number of people. One can, therefore, wonder why Aikido – as well as many schools of Jujutsu before it – puts such an emphasis on this type of training.

Grasping (,) the role of Uke

Why this surprising parenthesis? That’s not a typo. Much of the problem of Aikido can actually be summed up by the presence or absence of this comma. Is grasping the role of Uke, or should one grasp what Uke’s role is?

What is this role? Uke must create the conditions of the practice and therefore propose dangerous attacks, adjusted to the skills of his partner in order to help him improve. In practice, this is however rarely in place, and we will often see Uke grasp the wrist of his partner with much conviction and … wait for his response! Uke’s role is then limited to the action of grabbing.

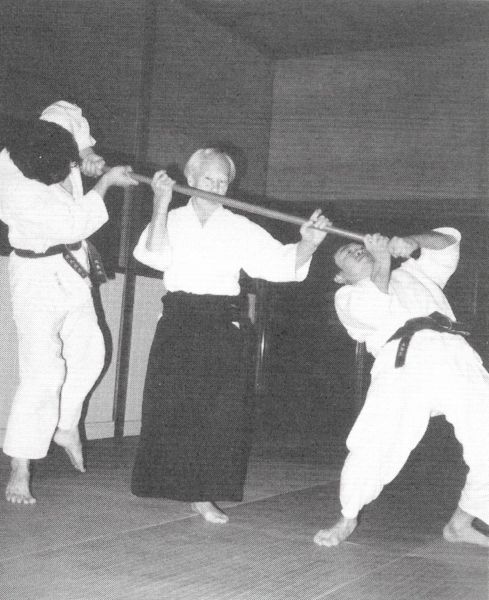

Uke must be dangerous. From a mere partner, he must then be considered a potential opponent, an enemy, Tekki. In this case, his action of grabbing represents the first contact between the two protagonists, and this grab must have a meaning. It can aim to throw, limit Tori’s ability to move, unbalance him to allow for a strike and finish the fight even before it actually started. When my opponent grabs my wrist, it’s to finish me, not for me to perform Ikkyo.

There can be so many reasons to grab a wrist: prevent the opponent from drawing his sword, throw, strike, or even protect oneself from the opponent’s initiative. But in all cases, the grab must be trained as seriously as the technique that follows. Without a real attack, there can be no realistic defense.

No one is grabbing wrists in the street

Another sentence we often hear, that is just as simplistic as the previous one. If Aikido is fortunately not limited to grabs (of wrists or other parts of the body and clothing), the “street” is also a complex environment that does not allow for any ready-made solutions.

If the rise of MMA has brought some fresh air, grappling arts and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu in particular have particularly benefited from the new trend, positioning themselves as the most realistic solutions. Wrist grabs, on the other hand, are much less present there than in Aikido, as grapplers often look forward to grabbing in some variation of the Judo’s Kumi Kata. Why then is grabbing wrists so important in Aikido, Daito Ryu and other Koryu?

The common carrying of a sword before the advent of the Meiji era is one of the most common explanations. Holding a wrist was then primarily made to prevent the opponent from drawing his weapon, while the techniques we learn would enable us to still take our weapon out.

Beyond this explanation, it may be interesting to look at the pedagogical contribution of wrist grasping as part of an “Aiki” art. Aiki as I understand it is the ability to control another person at the instant of contact, to cancel his ability to generate force. Holding a wrist in this setting is interesting because it is … difficult. A few years ago, when I asked Akuzawa sensei, the founder of Aunkai, why grabbing wrists and what was the point of Age Te (Kokyu Ho) exercises, he answered: “controlling the partner’s structure from the wrists is very difficult. It is much simpler if you get closer to the torso, for example at the elbows or shoulders. But the mechanics remain the same. If you can control a structure completely from the wrists, it will be very simple to do it from any part of the body. “

If you can control a structure completely from the wrists, it will be very simple to do it from any part of the body.

Akuzawa Minoru, founder of Aunkai

This, of course, works both ways: Tori must be able to control Uke from this grab, just as one must be able to control his opponent as soon as he puts his hands on him. The grab of Akuzawa sensei is an excellent example of that: from the moment he holds you, your structure is taken, it becomes impossible to perform any technique. At the moment of contact, it is over.

What kind of grab are we talking about?

Aikido is multi-faceted and each line offers its own tactical and strategic choices. The type of grab and the quality of the contact is one of these many choices. Some will apply heavy and powerful holds, while others will focus on lightness and sensitivity. These choices are not for debate as they have their reasons, but it is essential to understand where they are coming from.

In any case, grabs must have a meaning. That is to

When Ueshiba grabbed your wrist, it was already bruised. His hand was like a vise. Ueshiba could break the wrist just by grasping it

Mochizuki Minoru. Black Belt, 1980, “Aikido, lost in translation” by David Orange Jr.

Holding wrists – The Aunkai way

If unlike Aikido, Aunkai does not focus on the learning of techniques, it still includes a number of exercises starting from the wrists. These could be static like Age Te (上手, raise hands) or Sage Te (下手, lower hands), or dynamic such as the palms against palms walking exercises.

Aunkai’s primary objective is to develop a martial body, and these exercises are the cornerstone for that.

Bringing our hands down when held firmly in a static context is extremely difficult. First of all, the grab itself has an impact on our structure,

The same goes for walking exercises. Palms against palms and with outstretched arms, it quickly becomes very difficult to walk when our partner is not willing. Among the many reasons that demonstrate a bad use of the body, the difficulty to unify the body, from the torso to the wrists is a major one. I invite you to observe your own body, and in particular your shoulders, in Kokyu Ho-type exercises when your partner is putting a lot of pressure on you. Do your shoulders stay relaxed despite the pressure? If the answer is no, it is likely that your body is not unified.

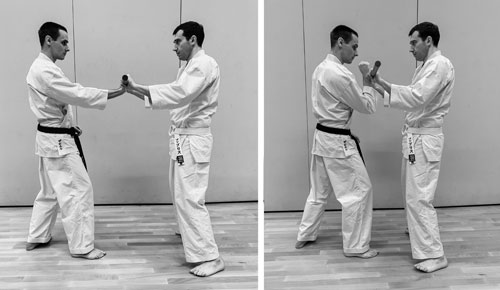

What does a unified body look like? A simple exercise allows us to

Now place your arm close to your torso, elbow down stuck to the body, forearm vertical and fist pointing up, and without moving your arm, walk. Is it simpler? No doubt, because your arm and your body are only one block now.

These exercises are obviously only exercises and it would be dangerous to confuse them with reality. But if you are able to easily take control of your partner while doing Sage Te, what prevents you from doing the same thing from a more realistic combat position? The same is true of Aikido, where techniques are probably less intended to offer realistic solutions to attacks as they may occur in reality, but to educate the body. If you cannot control your body, you will not be able to control your opponent, and unbalance him effortlessly under pressure in the most difficult conditions is key to creating an “Aiki” body.

From grabbing to striking

The modern separation between the arts of grappling and

If you are able to perform a heavy, relaxed, deeply affecting grip on your opponent, what prevents you from making a heavy, relaxed strike with the same effect?

Being able to deeply affect one’s partner right from the start, without relying on inflicting pain, is extremely difficult. Especially for practitioners who can only devote a few hours a week to martial practice. But I want to believe that this is what makes the great depth of Aikido and of its ancestors. The path is long and difficult, but isn’t it worth the trouble?