If you don’t ask yourself on a regular basis the “why”, “what” and “how” questions, chances are you’re going to hit a roadblock sooner rather than later. Your answers to these questions can of course vary greatly from the ones that are proposed below, and in all honesty, it doesn’t really matter as these are only potential responses fitting what we are trying to achieve. Your objectives can differ, and that doesn’t mean they are of less value.

Why should we forge our body?

Why is for me the one question every martial artist should ask himself on a regular basis. Why do we learn kata? Why am I told to do this form this way? Why do I have to bow that way? Every single thing you are taught in a class should have its importance. My opinion is that if it doesn’t matter, it shouldn’t be part of the teaching in the first place. But being important doesn’t mean it is explicit and that’s why one should always question what he does.

Back to our subject, why should we forge our body? Martial arts nowadays are often divided into two schools of thinking

– Internal (内家)that focus on how to move the body in a specific way

– External(外家)that focus on techniques

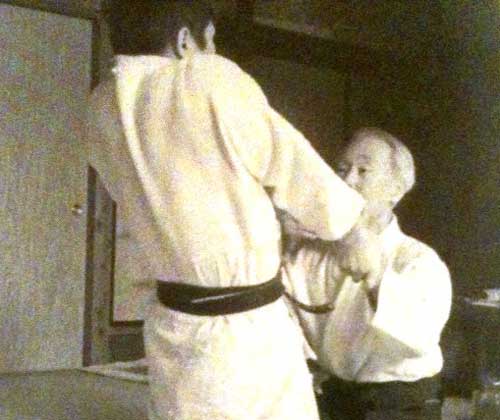

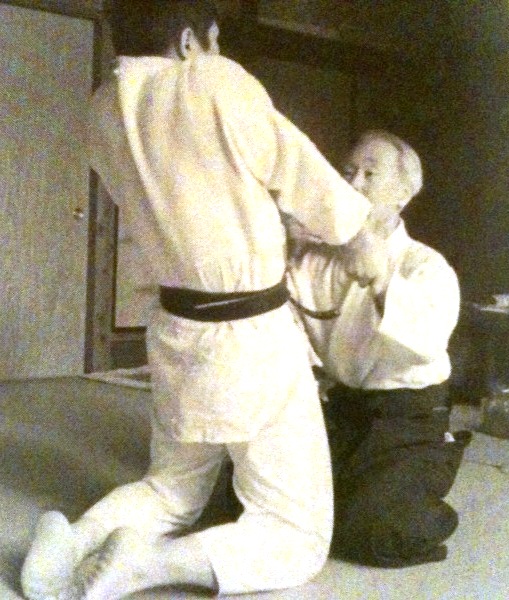

Sagawa Yukiyoshi of Daito-ryū was particularly famous for the way he forged his body

This remains a very rough distinction though as the truth often lies somewhere in the middle.

In this terminology, external arts (Karate, Aikido, Jujutsu for example) tend to focus on a number of techniques and patterns (kata) that eventually help create the proper body conditioning in the adept. At least in theory. Looking closer, if we hear a lot of Karate people saying that kata is made for fighting, very few Karate adepts can actually do so and that raises a number of questions.

Now, if we look at exceptional martial adepts, across all martial arts, one thing stands out: they all manage their body very well. There is no unnecessary tension, no unnecessary footsteps, they maintain their spine straight and keep their head well balanced, etc. It’s on this basis that internal arts focus first on building and managing our own body, before even trying to apply any technique. And that makes sense, how can you expect to control somebody else’s body if you can’t even manage your own…

It holds true for other physical activities as well. I remember a friend of mine, more than a decade ago, telling me about his time playing rugby at a high level in the junior categories. He mentioned a famous rugby player (Benoit Baby) that became international a few years later, and said “when he entered the field, he felt different. He tackled me once, then I always passed the ball before he could touch me. My ribs are still vibrating to this day”. What this story confirmed is that some people are just naturally well-knit together, and that makes everything they do just so much more efficient. For the rest of us, training specifically on building this body from the ground up can only be beneficial.

What kind of body do you want to get?

That’s a great question and I believe there’s no single answer to that as the body you want to get is highly dependent on what you want to use it for. In the Chinese arts, Bagua and Xingyi typically build very different skills, with Bagua focusing on twists and movement, and Xingyi focusing on a strong straight forward power generation. Both are great in their specific context, think bodyguard for the first one, and a front line soldier with a staff for the second.

Among the many types of body qualities you may want to acquire are attributes such as heaviness or lightness, having a unified body, or the opposite being able to dissociate parts of the body. And as if this was not enough… you potentially want to be able to do all of these and be able to go from one to the other in a fraction of a second.

When people think of Aunkai, they typically picture something static, heavy and highly connected. That can be true, yet it could not be further from the full picture. Akuzawa sensei can indeed feel extremely heavy, and his ability to connect his body is known by all, but at the same time he can move freely in a very light way, and his body is not connected at all times. Just the opposite actually as he tends to constantly dissociate/associate his body parts to enter.

Feeling heavy and connected is a great skill to have, no doubt about it. However, it also means you are likely to be slower, less agile, and easier to perceive. No one will move you in static exercises such as push out, but again these are mere tools, not objectives, and as soon as you go to a freer set up, things are going to feel very different, and probably overwhelming if your opponent is agile.

The opposite is true too. Being light and agile is great, but if overtime you enter on your opponent you feel like hitting a wall, there’s probably a part you missed.

My belief is you need to be able to shift your body “feel” depending on the situation. Move lightly, hit heavy. Dissociate to enter without being felt, re-associate once you’re in. Be light enough to accept the movement generated by your opponent, but be ready to shift your body to stop it when it needs be.

How do you achieve that?

Simple: come to the dojo, train, get inspired and do your homework!