This article was initially published in the French Magazine Dragon Spécial Aikido in July 2018.

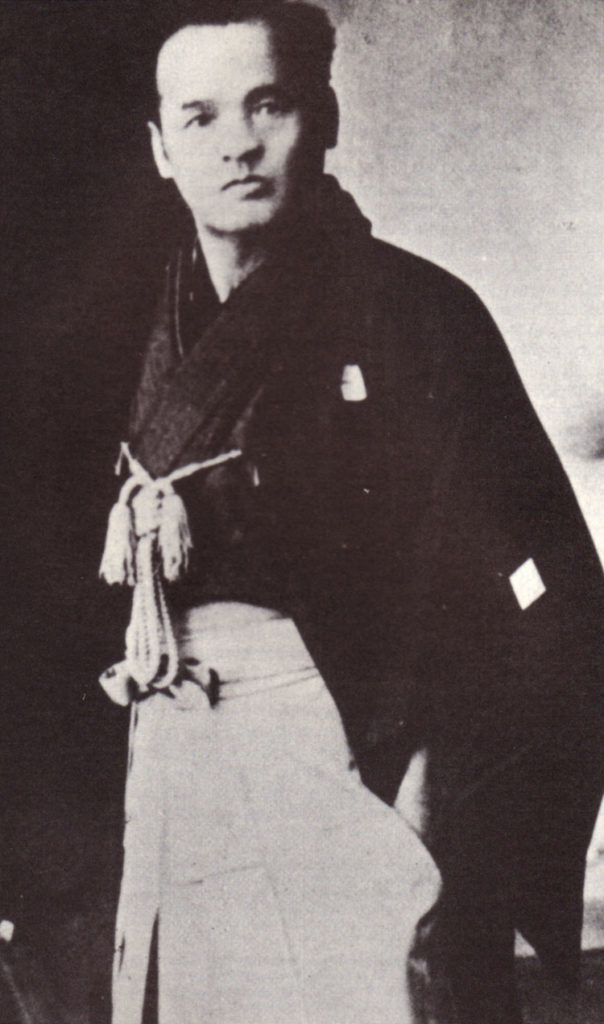

The question of the martiality of a martial practice can make one smile, and yet the simple fact that this question is asked so frequently with regards to Aikido already gives us the start of answer. There is, however, no doubt about the martial qualities of the founder, praised by more than one expert in his time.

Having trained in several martial arts before encoutering Aikido, this prejudice that I had was quickly confirmed on the mats. Lack of intention, surrealist attacks (and sometimes defenses as well), counting at least as much on the goodwill of the partner as on a technical aspect not always well understood. Yet in its essence Aikido retains all the elements to be a formidable martial discipline bringing my perception of the subject to evolve into two main questions after my beginnings: how did Aikido get to this point and how can we find back this lost martiality?

You attacked me wrong

The first plague of Aikido comes in my opinion from its attacks. A good defense cannot exist without a good attack. I have always found it sad in Aikido regular classes or seminars, with pretty famous Japanese experts to be told that I attacked badly and that was the reason why the technique did not work. While it is obviously possible that my attacks were not good enough, it is surprising that this had never been an issue anywhere else. But what is a “bad” attack?

A bad attack in the jargon of modern Aikido is most often an attack that does not create the conditions desired by Tori to apply his technique. Conditions that may vary depending on the research of the teacher and what wants his students to work on.

My personal point of view is that a bad attack is an attack that is not dangerous. It can be a powerless shomen uchi you see coming from miles away, a katate dori in which Uke grabs and waits for the riposte, a ushiro ryote dori in which Uke walks around Tori instead of attacking him directly in the back, by surprise. Examples of the bad attacks are legion in demonstrations, in which Uke runs around Tori waiting for a slight move of his hand that will indicate it is time to stop his race and fall.

Uke’s only goal should be to attack, to put his opponent in danger. In the old martial traditions of Japan, this role was regularly held by the most advanced person, simply because knowing the two roles of Shitachi and Uchitachi, the sempai was more able to perceive the shortcomings of his less advanced partner and put him under adequate pressure.

This more advanced role of Uke is not common in Aikido for many reasons. First because the rapid development of the discipline encourages practitioners of all levels to practice together and to attack each other. The founder himself does not seem to have particularly insisted on this or take ukemi regularly for his students, while his teacher Takeda Sokaku of Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu was famous for his paranoia and would clearly never have left his students apply their techniques on him.

But this structural change of pedagogy compared to the old traditions can not be the only explanation since this approach is shared by the vast majority of modern practices, Japanese or not. The problem lies more in attacking properly as Uke, with his attack, creates the conditions for learning. A real attack will push Tori into his last entrenchments and allow him to progress, while a simulacrum of attack can only comfort him that what he does is fine, leading to the famous “martial theater” that Hiroo Mochizuki criticizes so much.

This doesn’t mean that defining certain parameters, related to the way of grabbing for example, is of no value. The value of Aikido lies in its willingness to explore a subtle and profound way of doing things, and this exploration cannot be done in an entirely free context.

A few months ago, my Alexander Technique teacher told me that it is not possible to change the way we use our body when we are tired, when we are distracted, or when we are under pressure. This is a very important point to keep in mind when practicing Aikido. If an attack is to be potentially dangerous, it is not necessary to put our partner under systematic pressure. Intention must be present, but speed and intensity must be modulated.

These exercises are obviously not the reality of combat, they are tools that can develop certain qualities that will be useful in the context of a confrontation. They are necessary but not sufficient.

The question of responsibility is at the heart of martiality. Who is responsible when the technique does not work? Uke, who did not attack or react properly? Tori, who did not know how to adapt to his partner? The technique itself which was not effective or appropriate? In reality, these three answers are possible and are not mutually exclusive. Sometimes, Uke does not really attack. It also happens that the technique is difficult to apply in a specific situation, for example because of the relative sizes of the partners. But it also happens that Tori is at fault.

Intention is also an essential point, often left out. Aikido comes from violent practices, designed to incapacitate or even destroy an opponent. If its message today goes beyond that, it does not mean we must forget the context that gave birth to it. In a context of life or death, intention is natural. But at the dojo, people rarely feel actual danger. When I practice with Akuzawa sensei, the founder of Aunkai, I always have this moment where I really fear for my physical integrity. He never hurt me, and will probably never, but I feel his potential of destruction. Even before attacking him I already know that it’s going to be complicated, he’s got the upper hand. Same when he attacks me.

I am convinced of the interest of working on forms, in association with some personal research on body mechanics to understand the essence of practice. I believe, however, that these two elements alone are not enough to reach the highest level and that it is necessary to practice in free.

In Aikido, free practice usually comes down to two things: ju-waza in which more often than not Aikidoka find themselves practicing their forms on a variety of attacks; and randori in which several people attack like zombies and take ukemi as soon as Tori shows them a direction.

In Nihon Tai Jitsu, as in Yoseikan Aikido, free is particularly present and can be found in many shapes and sizes, along with different levels of intensity. It could be a randori against several opponents who really seek to attack, a randori with a single partner in which he can attack us but also counter our defenses should he have the opportunity, or sparring exercises in total opposition, whether standing or on the ground. It is the same in Aunkai and I do not remember a training at Tokyo’s Hombu dojo that did not end with kuzushi, a free practice in opposition where each partner must seek to preserve his body structure while breaking that of his opponent.

Conclusion

Aikido, in the way Ueshiba Morihei offered it to the world is a martial discipline of rare quality. The presence of advanced practitioners from other martial atys among Osensei students is one of the best evidence of this. The massive development of the discipline and its message of peace, attracting today a wider public, have however had a devastating impact on the martiality of Aikido, which is struggling today to demonstrate its effectiveness. All the elements of this martiality are nevertheless present within Aikido, and this even if they struggle to be visible. It is up to us to seek to restore Aikido’s past martiality by objectively looking at our shortcomings.