This article was originally published in French in “Dragon, spécial Aikido” number 20, in April 2018

When one thinks about moving in Aikido, one immediately thinks of Tai Sabaki, and more specifically Irimi and Tenkan, which form the basis of the discipline. And yet, before going into a discipline-specific way of moving the body, it seems important to take a step back and simply understand … how to walk.

Walking is one of the most basic human activities. The human body is not designed to remain static, but on the contrary to be in motion. If you have any doubt, think of what is easier between standing still for an hour or walking for an hour …

Walking patterns matter and it is always interesting to observe the greatest adepts and the way they move. How do they make contact with the ground? Are their steps heavy or light? Do they push into the ground or do they use a different mechanism to move forward? What does their center of gravity do? And how do they transfer their body weight? Personally, I am convinced that there is not only one way to walk, but that the chosen way necessarily has a strong impact on the rest of the practice and that we must therefore be consistent from the first step onward. It is indeed rather difficult to reconcile the ways of walking of some of the greatest contemporary adepts, and to be honest I do not think they even need to be reconciled.

Increasing body awareness

One of the first goals of martial practice is to significantly increase our body awareness. Of course the ultimate goal is surviving and handling our opponent, but in order to control the body of a third person, we must already be able to control more or less correctly our own. What differentiates in my opinion the greatest adepts from ordinary practitioners is often the ease with which they perform their movements, their mastery of fundamentals. This is true for martial practices but also for any physical activity. My Alexander technique teacher was taking the example of Cristiano Ronaldo in football and Roger Federer in tennis, two of the biggest stars of their respective sports. And indeed by watching them move, we can note how well they manage their body, much better than the other athletes surrounding them. This is particularly noticeable if we look at how they balance their heads. Note it is not necessarily something conscious or acquired, but more likely innate qualities that allowed them to reach the highest level. However for us mere mortals, it is not forbidden to go back to the basics and try to correct our mistakes, however small they are, to get closer to this natural ease of the greatest adepts.

Walking his first steps on the mat, a beginner rarely has a great body awareness, neither does he know how to handle it in space. Of course he had a life before martial arts, a life in which he walked since his toddler years, but most likely in a way that was not particularly mindful. The practice of Aikido or any martial discipline must help to refine this awareness, and to a certain extent it does. To a certain extent only because martial practice offers a work that is much more complex than these basics, at least in appearance and easily encourages the ego to take the light. Who among us has not tried to bring his partner on the ground at any cost to the detriment of the integrity of his own structure? Off balance, a shoulder rising and bracing, the head unbalanced, you name it. Working on techniques is obviously useful, but has the disadvantage of making us easily lose sight of the deeper work we need to do on our body.

Some schools, on the contrary, especially in internal arts, put a strong focus on basics such as standing, sitting or walking. That’s typically the case of Aunkai that made these three elements its motto, but if we look on the Chinese arts side we can also note the critical place of walking. Bagua Zhang, for example, is famous for its circle walking around a tree, while Taiji classes usually start with slow-motion sideway walking exercises, allowing the practitioner to become aware of his posture and of the muscles he put into action while walking.

Putting the foot on the ground

Walking requires the simultaneous action of multiple body parts and it is obviously impossible to describe them all in a single article. But among them the use of the feet, acting as the only points of contact between the body and the ground, is of paramount importance.

Here again there is not a single way to do things, and they highly depend of the selected practice. For example, you could choose to put the heel first and “unroll” the foot to the tip, or to touch the ground with the front of the foot first, sometimes even not putting the heel on the ground at all. In my case I favor putting the foot flat on the ground, which of course is more complicated to do with shoes on, as these commonly have a slightly raised heel. For that reason, I prefer wearing “barefoot” type of shoes.

The laying of the foot has immediate consequences on how we use the body. By walking on your tippy-toes for example, your calves get more engaged, as well as the back line of your body. In this way it is possible to push into the ground quicker and be explosive, which explains why it is the preferred method in combat sports. Standing with the weight on the front of the feet, however, makes it more difficult to use your structure and skeleton optimally, and will require more effort and time to change direction. This is not a concern in combat sports, but it can be in a more open context with a number of opponents. One can easily imagine that the 1-on-1 context of boxing, going on for a few rounds does not have the same requirements as a 200 against 200 battle lasting for several hours.

On the contrary, a flat foot makes it possible to better use your body structure by letting the weight of the body fall naturally into the ground. When standing, the human body is designed so that the weight should fall more or less in the feet at the level of the malleolus, if it falls further forward or backward, a number of muscular chains will have to to be engaged to compensate.

Generating movement

How we put our feet on the ground is only one of the many things to consider when walking. The second most important element in my opinion is the way the movement is generated. Once again, plenty of options and each and every one of them has direct implications on the rest of the practice. To get an idea of the diversity of choices, just take a look at people walking in the street and observe what muscles are involved and what consequences this has on the way the person moves. The methods used by each individual differ sufficiently so that one is often able to recognize a friend from afar, just by the way he walks. I remember a winter day in Tokyo when I was waiting for Akuzawa sensei, trying to spot him by watching people walking through the park, wrapped up in their coats, scarves and hats. I recognized him quickly without the least moment of doubt, at a distance that did not allow to recognize any of his physical traits, as his way of walking is quite unique.

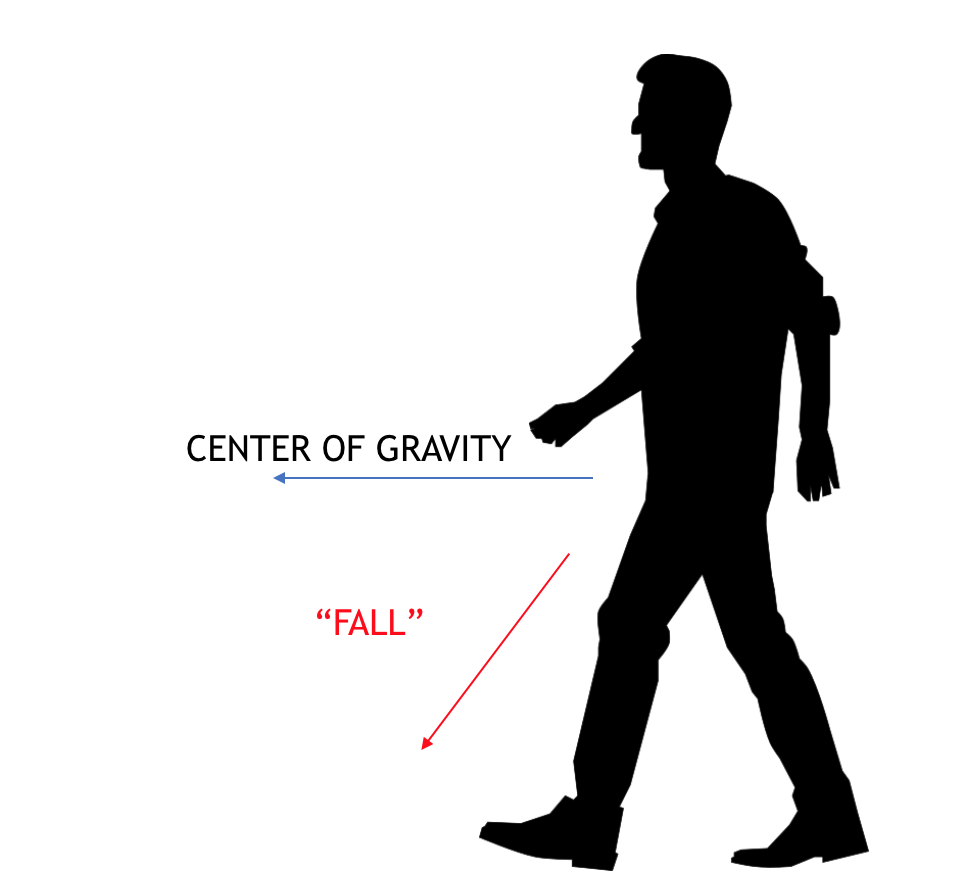

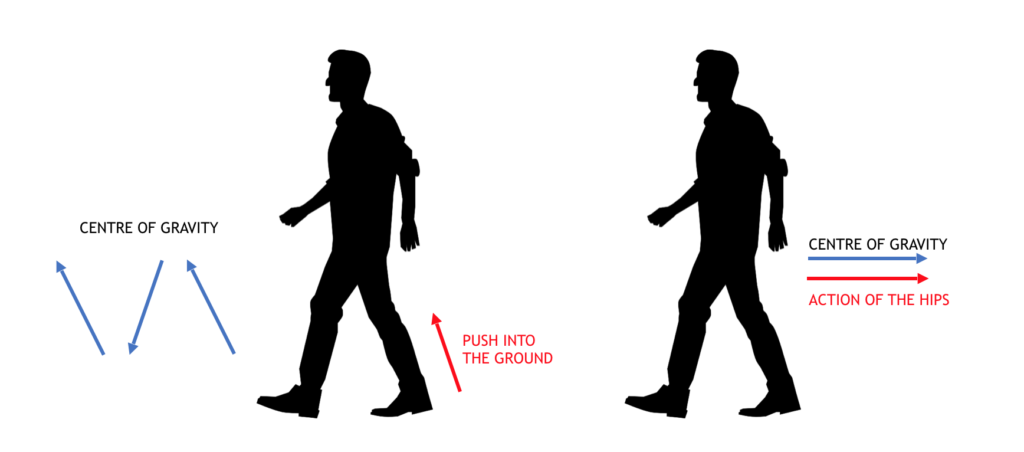

Not pushing into the ground and managing one’s center of gravity are the two points I emphasize the most when I introduce my way of walking to martial artists. Both are related and I like to propose the following exercise to see how. In pairs, one of the practitioners walks in a natural way forward. During the walk, his partner pushes him in the back, which usually causes a loss of balance before catching up. They then retry the same experience but this time with the partner walking backwards rather than forward, and pushing him on the torso. The result is usually very different and the balance is maintained more easily. This difference of outcome is actually very simple to explain. Our knees and ankles are designed to go only in one direction. When we walk forward, we naturally tend to push into the ground, which has the effect of raising and lowering our center of gravity at every step. When walking backwards it is much harder to push in the ground, so movement is normally generated from the hips, while the back stays straight and the center of gravity moves linearly backwards.

What should be your takeaway from this: walk forward as if you are walking backwards.

Among the kunren of Aunkai, “walking maho” is one of the best-known exercises. Palms in contact, the partners face each other, one walking forward, the other backwards, providing feedback to his partner. If one kicks the ground to go forward, the feedback is immediate as the force is transmitted directly from the back foot of the person going forward to the back foot of the person receiving, and thus directly into the ground, making it particularly easy to nullify the received force. It then becomes necessary to find a different approach to be able to go through. One option is to slide the pelvis down and out, or in other words to… fall from the pelvis. What is walking indeed if not falling from one step to the next, catching up with the help of your legs? Conversely you can also choose to initiate you walk by “pulling” the chin.

An endless job of introspection

The elements presented above are voluntarily limited as you would need to write volumes to describe precisely all that’s happening in your body while moving. And this would only represent what is happening using ONE way of using the body among a great number of them. At best these elements can be a starting point when addressing the subject of walking, and more broadly of every type of movement. On the temple of Delphi are written the words : “Know thyself”. Thousands of years later, this quote is still relevant to martial practice, and I can only encourage you to observe deeply how you stand and move. It is an endless work, easy to put in place and feasible in every place at every time. The work of a life and the basis of a practice more richer and deeper.